Re-membering

I will begin with memory this time.

It was Lahore. December, 1971. In the bubble that I lived, which consisted of one of the Christian hospitals in the city, residences for doctors, the nursing school and its adjoining hostel, and various apartments for employees, there was a wee bit of hubbub. I remember finding out that we were going to war, or rather, India had declared war on us.

I was seven years old, closer to eight.

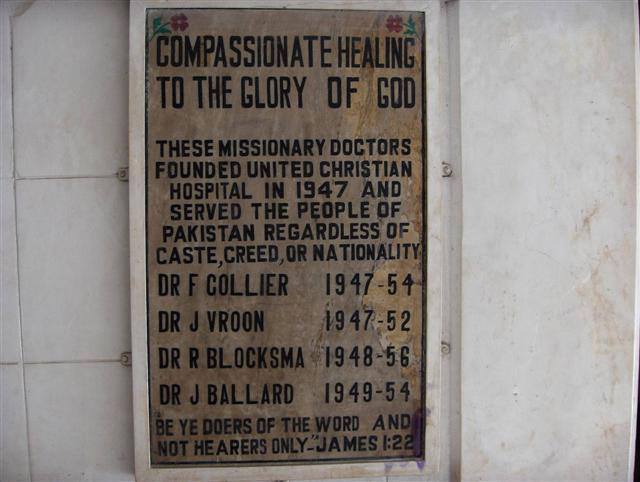

Usually, my siblings and I were not allowed to go in the hospital where Benji was the Medical Director at that time. The first desi to be selected as such after all the years that Americans had been the directors since 1947. The hospital, as it was in 1971 was the newer version of what had been set up almost 25 years ago by American missionaries on the Forman Christian College campus, during Partition. The plaque upon its foundation stated that the doctors served the people of Pakistan regardless of caste, creed, or nationality – an important statement to have made in that time of crisis, when people were killing one another, for those three.

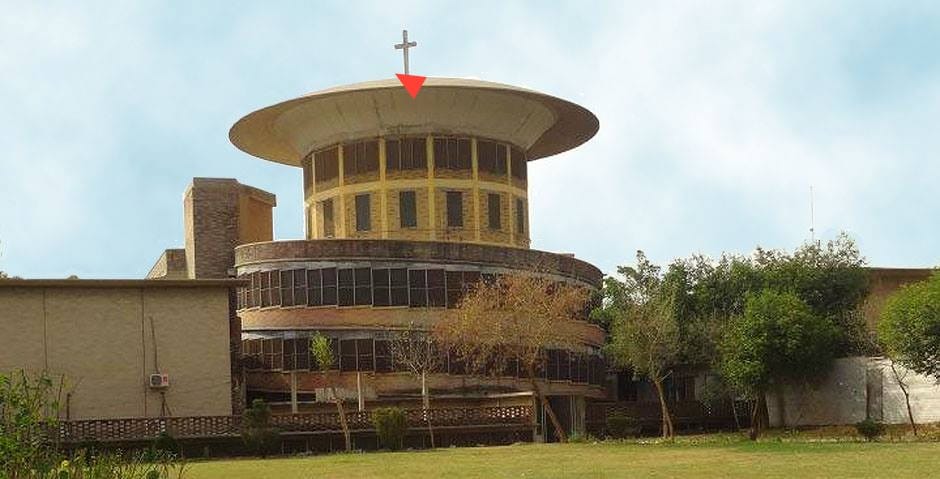

On that day in December, when we had confirmation, we were allowed to go in the hospital. Our American neighbors and we were planning to shelter there if and when Lahore would come under attack. There were trenches in our neighbors' gardens. Our houses all had entrances to the tunnels, should the need have arisen to use them. Outside, on the hospital building, maintenance workers were on the dome, painting a red cross on it. Someone told me that that might keep the hospital from being bombed.

It all felt so unreal. Some of us kids, especially the boys, who played war with toy soldiers, were a wee bit excited about what was to come. I don't remember what I was feeling. I didn't understand what was going on. In my family, children weren't always part of conversations that involved adults, and what was shared was on a "need to know" basis.

I recall that day, one of the first places we children went to in the hospital was the Central Supply department. The people in charge let us prepare gauze bandages to be sterilized in the autoclave. With every bandage I prepared, I hoped some would go to the war wounded. They were intended for filling the regular quota for patients, as I would find out, so I was still being of service – just not for the war, alone.

We wandered through the spiral hallways, avoiding the wards, lest we should run into Benji and be loudly scolded, and some of us went our own separate ways. I headed for the cafeteria, where a number of people were gathering. No one looked familiar to me, they may have been relatives of patients, or families of employees I had not met. Many of them were women. My introverted self looked for a seat where I could sit by myself, with the feelings of confusion and dread that were rising within. It was too much. I went in search of someone, anyone I knew.

. . . . .

Whenever I hear sirens that go on for lengthy periods of time, like at factories, for example, or even red fire truck sirens that one can hear from blocks away, I think of the day I ran for my life.

One day, when all was quiet, my little brother and I were at home with Mum. We had just finished lunch, when Mum told us we should go back to the hospital where it would be safer. The red alert siren began as soon as we approached the pathway between the lattice wall and the field.

"Run!" One of us yelled. My five-year old brother and I ran as fast as we could. He ran faster. I was never able to run as fast as most children. We heard the aircraft's loud engine. It felt so close. We managed to make it to the door as it flew over us.

I believe neither of us knew at the time whether that was one of ours, or India's, but that moment was the first time I truly feared death. Even if it had been one of ours, it was a frightening minute.

. . . . .

"We saw a dead body!" One of my brothers shared with me, animatedly. I, wanting to do a number of things my brothers could, asked them if they could take me to it.

"No!" Little brother scoffed. I don't remember him indicating whether it was someone killed in war, or not, but I was determined to see one for myself. Both my aunt and a maternal cousin were nurses. I begged them to help me. At first they refused, but finally gave in when I would not stop pleading. We had to be careful though. We had to go at a time when Benji would not be making rounds. It had to be in the evening. No one else could know we were doing this. Having experienced my father's violence, more than once in my life, I did not tell a soul.

I was not able to track where we were going, directionally, given how anxiety-ridden I was. We arrived at a room with a bright lightbulb hanging from a longish wire. A body was covered from head to feet in a bright white cotton sheet. Just as one of my relatives had begun uncovering the face I realized was a man's, we all heard a booming voice,

"What are you doing?"

I was frozen with fear. Before I knew it, Benji came at me and whacked me hard on my weak back, bringing me to tears. He pulled me, and his youngest sister by her long hair towards the door, he left my cousin untouched and shouted at us to go back upstairs.

I was sobbing. Phupho was crying. I felt bad, not only for myself, but that all of us had to go through what we did, and I wished I had never asked them to take me to see the body of someone who had been a patient, as Mum would tell me later. It was not a soldier or a civilian who had been killed by the bombs the Indian Air Force were dropping on us. I don't remember Phupho or Bāji telling me who the man was.

Most of what I remember about that night is my father's violence. Violence in what felt like a very violent world. One that many were not shielded from, outside the bubble we were in.

Benji did apologize to me, not long after we returned to the hospital cafeteria. The apology that justified his anger because I did something I should not have done, but for me, never justified his behavior.

It would not be the last of such apologies.1

. . . . .

Before Pakistan preemptively attacked Indian bases in the first week of December that year, its army had been in a months long war with Bangladeshi liberation fighters, the Mukti Bahini. From March 1971 through December , when the Pakistan Army capitulated once India entered into the war, the Pakistan army (it was still West Pakistan for them, since they were fighting to control the East wing) relentlessly attacked and slaughtered whom they supposedly considered fellow Pakistanis, and raped women. Hundreds of thousands of Bengalis massacred in what more than a few in Pakistan would still consider a civil war, but it was Genocide.

Countless refugees crossed over to India as the Bangladesh Liberation War continued, and the refugee situation was in part what prompted India to help them. This enraged Pakistan, and led them to attack Indian military bases (air force), which gave India the opportunity that some may have waited for to declare war on Pakistan.2

. . . . .

Partition was not without its discontents. When Pakistan became a nation, based mostly on Muslim populations, both West Pakistan (Punjab, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa- formerly NWFP, Balochistan, and Sindh) and East Pakistan (formerly East Bengal), were governed as one body. This one body had a great big land mass between them: India.

Every region, including the East wing, has their own language (even polyglot). Urdu has always been the official language though, but mostly used within the four provinces. In East Pakistan, Bangla was mostly spoken. Bengalis wanted their language to be accorded official or federal status alongside Urdu and English, but that was not to be. Given the high percentage of Pakistanis who spoke Bangla, many in the east began a movement to elevate their language. One of these protests was violently crushed by police resulting in deaths of civilians, including students.

Political power was housed mostly in the West. Nowhere was that more glaring than the 1970 election, when the Awami Party, based mainly in the East, was said to have won by a landslide. The West did not accept Awami's victory.

Language, and political power were not the only issues that led East Pakistan to believe that liberation was the way to go. Bangladeshis overwhelmingly felt that they were neglected by the West, and exploited at the same time, and they were ready after two decades to declare their independence from Pakistan, which they did in March, 1971.3

Pakistan finally recognized Bangladesh as a nation-state in February, 1974. I actually remember this because Pakistan hosted the 2nd Islamic Summit Conference in Lahore. I watched it being televised, and Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the Prime Minister of Bangladesh was present at that conference. They recognized Bangladesh on the very first day.

I am most likely writing all this more from the Bangladeshi point of view than the Pakistani, or at least that is how it would be seen by Pakistanis. But I am also writing as someone who is still learning about this horrifically violent rupture, and as someone who has always been attached to the land of their birth, but yet, always as an outsider looking in.

. . . . .

On a personal note, connected to 1970-71, one of my uncles worked for the Pakistan Civil Service. He had been working in Islamabad when we returned to the homeland sometime between Spring and Summer in 1970. His superiors wanted to send him to Bangladesh in the midst of the Liberation War.

He refused. This uncle was politically active through his college years. He railed against Ayub Khan's crackdowns on students, among others in the 1960s. I don't know that he refused to go out of political conviction though. I believe he wanted to see his three children grow up, and there was no guarantee he could do that were he to go to Bangladesh.

I, for one, am glad he refused. What made me sad was how this once bright young man was blacklisted, and unable to work for any service within the Pakistan government ever again. He moved his family from Islamabad to Lahore, and thus closer to two siblings who loved him and got to see more of him. He knew what his choice would cost him and he made it anyway. It's hard not to think that cost changed him though.

- My father was definitely not an easy person to live with, or work for, as I did. He was quick to rage first, and sometimes regret later. As a doctor, he got more rave reviews than he did within his nuclear family. I would not be here without him though, and I don't mean as him being just a sperm donor. His no longer being physically violent once we returned to the US did not mean we were without scars.

- Some of this is also developed in Gary J. Bass' The Blood Telegram: Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide. Knopf: New York. 2013. I wanted to write more about what I've read about the US involvement, or lack of entailed, and how Nixon's support of Yahya Khan and Pakistan is in Bakhtinian dialogue (apologies for the literary theory!) with the U.S government's support of Israel, especially with the ongoing Genocide. Being in dialogue, doesn't mean comparison. I'm thinking more in terms of how U.S foreign policy of the past is never quite the past.

- Some information gleaned from the Wikipedia page regarding the Bangladesh Liberation War, here. For those dismissive of Wiki (sometimes with good reason), this was not meant to be a scholarly paper. Not that I needed to explain that.