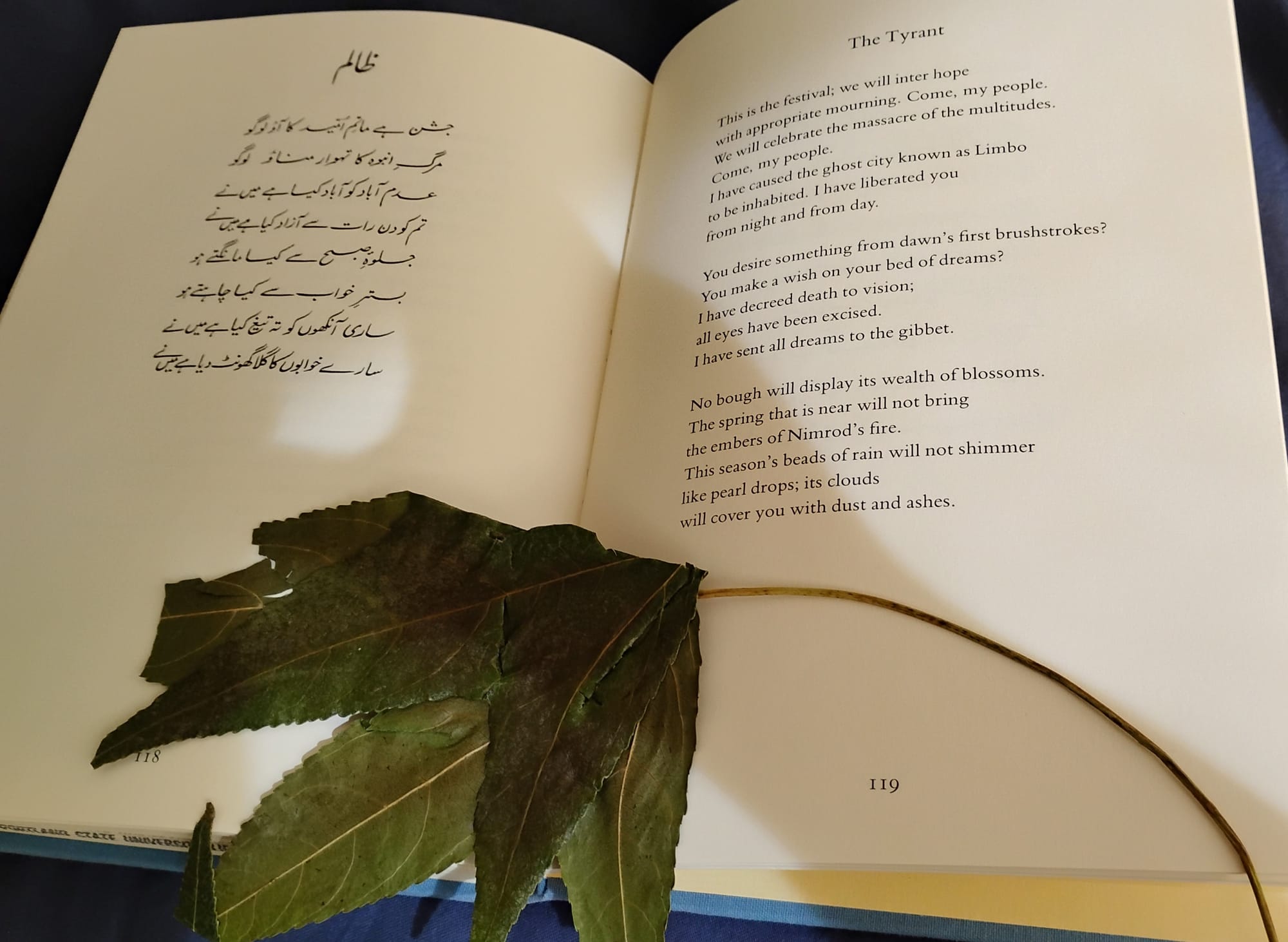

Zālim

I haven't written a post here in a long while, and there's a reason for that. When I'm experiencing high anxiety, I find it difficult to coalesce thoughts together. Or if I do, it's in short notes, like on Substack.

I've been super anxious for months now. I was already experiencing anxiety and chronic depression, but since the escalation in Gaza and now the West Bank, and the dictatorial moves of this government, that anxiety has doubled. I know, I know, I have no control over any of these events, but telling me that is totally unhelpful. When a friend says What can we do?, I am doing what I am able to do, or what I have to do to survive, and live.

Before I dive into the salad of my mind, a bit of housekeeping. I am not renewing my subscription to Ghost, so at some point in the not-so-distant future, I will be returning to write on Substack, provided it does not succumb completely to any demands that jeopardize the many awesome voices there.

. . . .

When my family moved back to the US in 1979, I really had hoped we would move to a bigger city like New York, or San Francisco, but we moved to a rural American town. And if any of us experienced cultural shock, baby, that was it. I'm not dissing rural America, the city we lived in while in Pakistan, Lahore, was the second largest, population-wise, at that time we were there, with approximately three million people. A city that, unaware to more than a few Americans, had running water, electricity, shopping centers, a museum, decent restaurants, smoke-filled coffee houses, tons of cinema halls, excellent schools and colleges, an international airport, a cantonment that housed a number of military families, hospitals, most importantly many intelligent people with varied political leanings . . . . hopefully you get the picture. And why should Americans have been aware that such places exist in Pakistan?!?

We moved to a town of 3000 Americans. A chunk of whom had no idea where Pakistan was.

Mostly White, a considerable number of Mexican-Americans, some who had come as migrant workers, a number of Japanese-Americans, and very few Black families. We were the only South Asians in town. The closest metropolis to us was Boise, Idaho, which also gave a more rural vibe than it probably does now.

We lived in that town until my youngest brother graduated from high school, until that point, my older siblings and I were hardly at home, because we were at university, and only returned home for holidays.

. . . .

I don't know that some ever thought of me as a full Pakistani when I lived in Lahore. I had an American accent, I didn't dress like most Pakistanis - one of my classmates even said I was an American, because she saw me wear shorts when I accompanied Mum to market. And, I wasn't Muslim.

I will say this, even though I still firmly believe that there was some structural discrimination at the school I attended, no one ever told me to go (back) to America because I was Christian as some would, years later, to Christians when the violence against the community increased in the 1990s and onward. As if America was where Christianity began (I know, don't tell me that's what a few here might think!). I felt I was as Pakistani as those who'd lived there all their lives. I loved my city. We would not have left Pakistan, had Benji not told Mum that he wasn't coming back (I still think he was trying to leave her even then). But had we stayed, it would have been harder on the older siblings who could never quite get to the level of Urdu that my youngest brother and I did. They could speak it, yes, but they couldn't read or write it. It would have been hard for them to continue their education in Pakistan.

When we left Minnesota to return to Pakistan in 1970, my eldest brother had just ended first grade, and my sister, second grade. We learn Urdu from kindergarten onwards in schools in Pakistan. We were all at a disadvantage already. I remember how Dadaji (paternal grandfather), who had been a primary school teacher, taught us the Urdu alphabet. We all had our takhtis (slates) and writing utensils, as we made shapes with and without dots that had been completely unfamiliar to us, until then. The entire time I was at school, I hardly ever passed an Urdu class, the times I did was barely, and the fact that I was promoted every year, I owe to my marks in English, and History, and some other classes. Not Urdu or Math. Even now, perhaps my accent would give my not being a native speaker away, but my not being able to tell between masculine and feminine, as verbs are gendered according to the noun, definitely would.

When Zia established Martial Law in 1977, much as I may not have wanted to leave Lahore, I was ready to go. I was already seeing what we would have to give up to stay, and already being "second-class citizens" was hard enough, I didn't want the additional tyranny.

I wonder if Faiz wrote this during Zia's time. We've had more than one tyrant. The title above Faiz's poem is Zālim. I've referred to Zia as Zālim Zia for years.

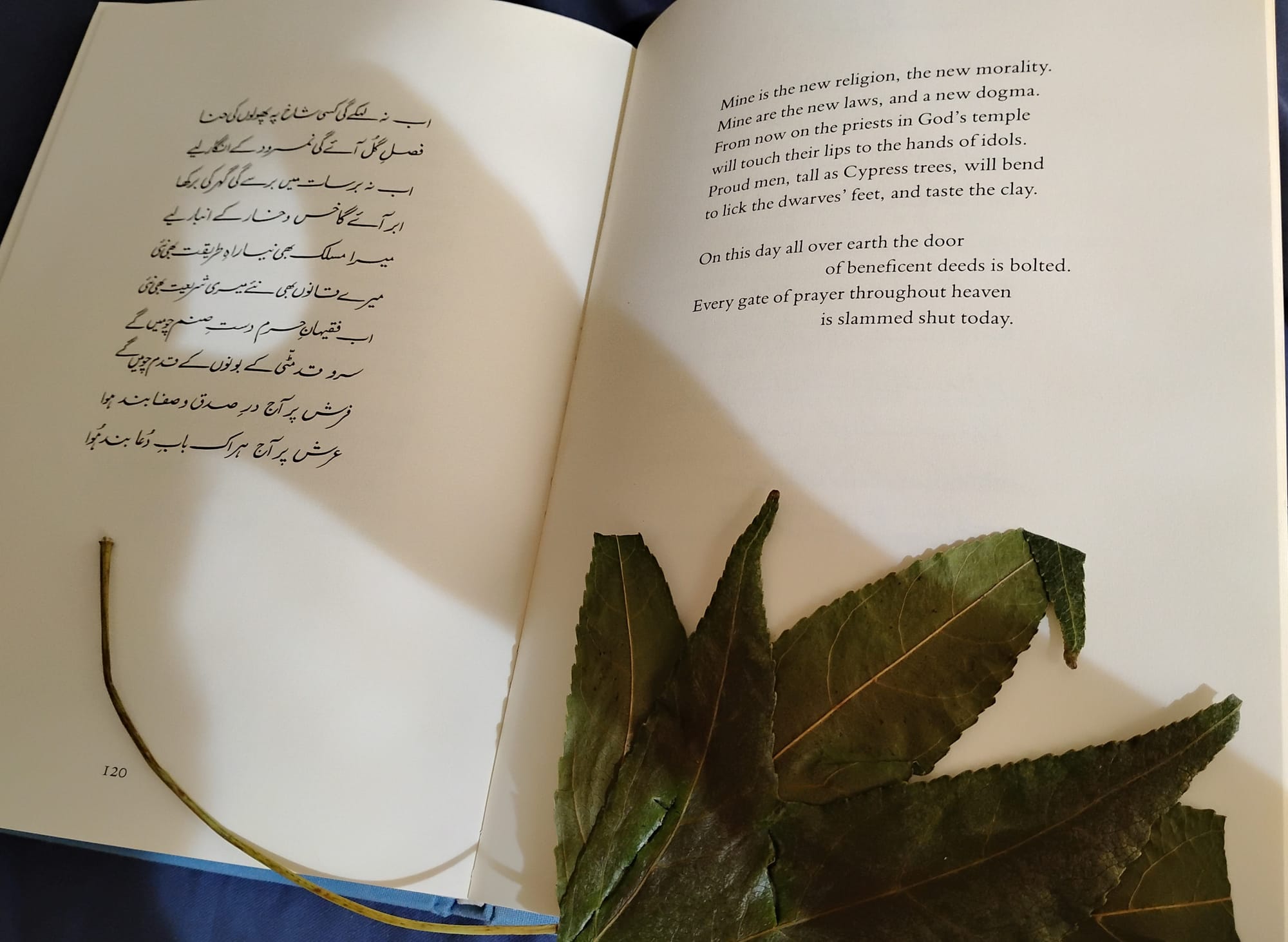

The whole poem, written from the tyrant's point of view, hits hard, but the part directly above hits even harder. And when I read this in the context of what is happening in the US today, what is happening in Palestine, for me, this poem connects. I've thought of this poem often in the past few months, and one of the reasons I was in search of this book, was to see if it relates.

. . . .

Here, I often felt as if I were straddling two boats, as far as my cultural identity was concerned. I've felt at home here, that I belong here. But reminders of what some people think of those with my complexion, and darker still occur: the lock of the door of a car that's been occupied and in place for a while, as I walk by, the piercing hostile stares as I board public transportation in town, and the slurs. Still, there was a point where I felt I could just be in one boat, bring the Desi in with the American, because what is American culture after all but a mix of . . . . vinyl scratches all the way to the end.

This administration has made it very clear how they feel about Brown people, Black people, Queer people, Trans people, Muslims, Women, anyone who does not fit their view of Christian. To refer to the poem above, theirs is the "new" religion, morality, and dogma. It really isn't all that new, we know.

I belong here. I have felt more at home here than I did in Lahore, in terms of more freedom to be me. But this government, and many of its people no longer think that way. The melting pot, which was a terrible metaphor to begin with, only works for this administration if you come out of it as a white male Christian nationalist. Homogeneity requires compliance. And if we don't comply, they will try to do their utmost to make us, or punish us.

As an immigrant who has lived here from adolescence through all of my adult life to this point, I have often considered leaving the US, but I still have family here, and friends, and a support system should I ever need one. Also, it's financially unsound to leave. I feel like I owe it to all of us to remain, to not let tyranny win. But the future right now is incredibly murky, and it feels more unsafe than ever. There are MAGA voices that dump on the city I live in, and call it a shithole, a dangerous place to live, filled with leftist agitators, all the things that they'd find reason to come in and take over. My city has plenty of issues, but it is not the problem they want it to be. If it feels unsafe, it definitely is not because of this city, where I have lived most of my life, which is home.